Preservation vs progress

A tale as old as independent Singapore.

Pedestrians walk by, unfazed by a cacophony of power tools whirring and roaring. The noise feels deafening even with the towering sound barriers. Signs apologise for the inconvenience. It seems like you can’t go a block without spotting a construction site, workers sweating under glaring sun in the thick, wet Singaporean air. These plots of dirt and rubble littering the island will become modern, multi-storey buildings. Fresh. Clean. New.

According to 2023 research by Stacked Homes, most residential projects in Singapore are redeveloped after 19 to 24 years. This means new construction is torn down, on average, barely two decades after being finished.

Heritage sites are dwarfed by residential buildings. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Heritage sites are dwarfed by residential buildings. Photo: Chloe Henville.

With the omnipresent evidence of advancing infrastructure, thoughts turn to the short, squat properties of the past. The heritage buildings.

Construction supplies block tourist hot-spot Marina Bay Sands. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Construction supplies block tourist hot-spot Marina Bay Sands. Photo: Chloe Henville.

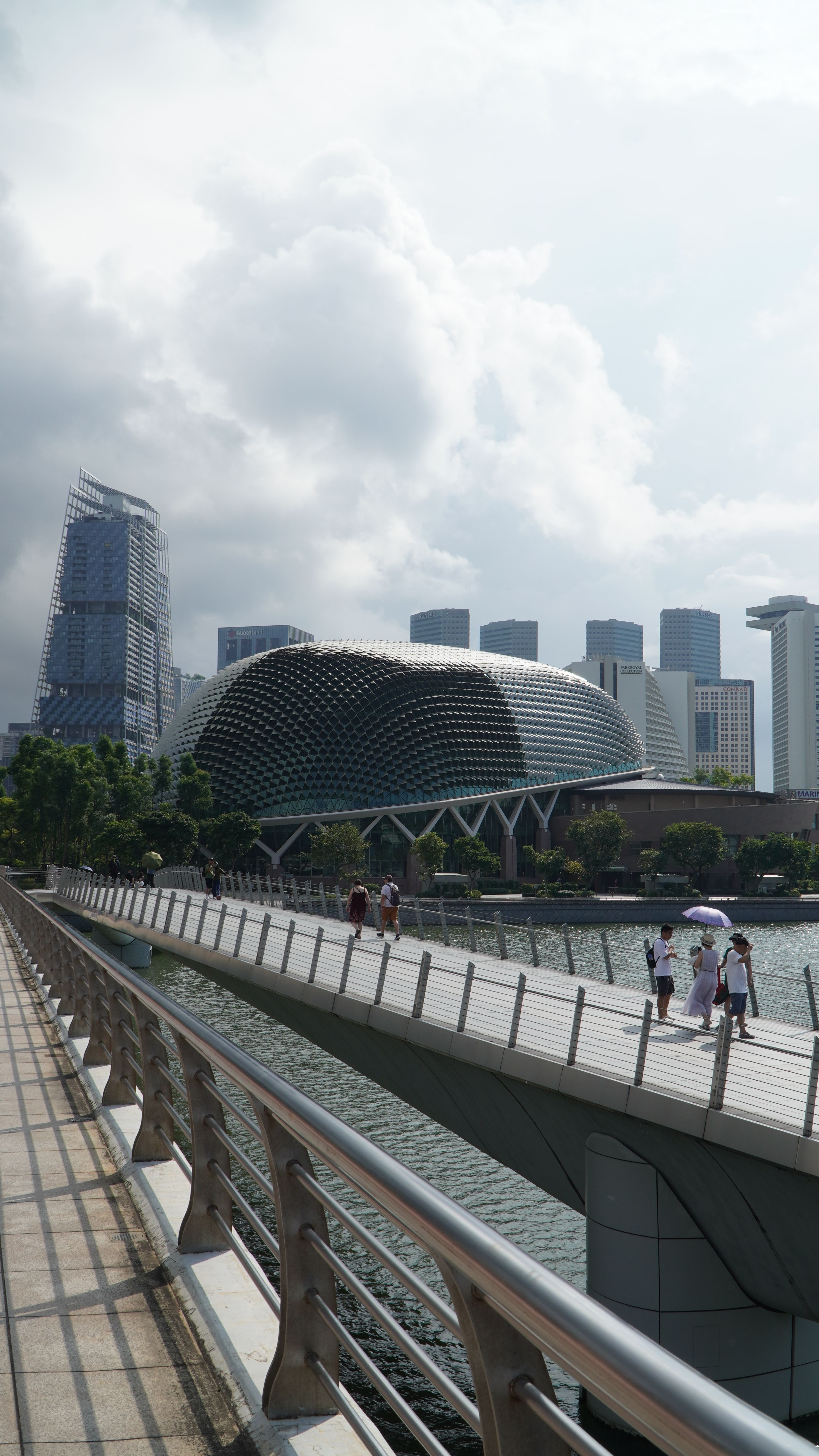

Glass and steel make up the modern city centre. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Glass and steel make up the modern city centre. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Old and new designs collide. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Old and new designs collide. Photo: Chloe Henville.

141 Neil Road is an unassuming building nestled in a row of terrace houses. From the footpath, the crumbling façade is hidden by a tall, slatted fence. If you take a step back and crane your neck, the second storey pokes out with defiantly shuttered windows and ornate plasters designs which are creaking and cracking.

The exterior looks rundown. Photo: Chloe Henville.

The exterior looks rundown. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Stepping through, you’re greeted by terracotta floor tiles, and plaster walls skirted in floral painted tiles. The original features and elaborate details are foggy with over a century of use and disuse. They’re waiting to be polished to a former glory - a raw diamond to be cut to show its’ brilliance.

The first floor shows original features. Photo: Chloe Henville.

The first floor shows original features. Photo: Chloe Henville.

The shophouses’ 1880’s time of birth is very rare for Singapore.

Barely 6.9 metres wide, it has a footprint of just 297 metres squared.

“It's a small building, it's not a grand building, only two and a half stories,” says Dr Nikhil Joshi. “It's [worth] nine million dollars.”

Dr Joshi proudly wears a custom shirt showing the shophouse. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Dr Joshi proudly wears a custom shirt showing the shophouse. Photo: Chloe Henville.

But to Dr Joshi,

this specific shophouse is worth much more than its land value for developers. It’s located in the Blair Plains Conservation area.

In 1986 the Urban Redevelopment Authority launched its Conservation Master Plan, earmarking six historical sites for conservation, including Little India and Chinatown. This marked a shift of government priorities, pushing preservation to the forefront, alongside redevelopment.

However, decades later, government intervention may not be drastic enough. Hurdles to conservation are still present, and time is running out to protect Singapore's architectural heritage – once it’s gone, it’s gone.

ArClab

A group of passionate academics have decided to dismantle these barriers with a pragmatic approach. 141 Neil Road is now an Architectural Conservation Laboratory owned by the National University of Singapore. It’s a ‘living laboratory,’ a hands-on hub of education about preserving architecture. Dr Joshi, senior lecturer in the department of architecture at NUS and the director for ArClab, says historically Singapore wasn’t aware of the importance of heritage preservation and it's an issue the country still battles with.

As a small island country, land value is high and these old buildings don’t use vertical space well. In comparison, a skyscraper creates space and opportunity for business and economic prosperity. Dr Joshi says ultimately, money is prioritised, at the expense of heritage building preservation.

“These buildings were demolished completely. Gone,” he says.

“Now it also happens. Even now there are buildings which are demolished every day. Beautiful buildings.”

- Dr Nikhil Joshi -

He gestures passionately out the open door of ArClab towards a construction site across the street.

“There was an apartment there, beautiful apartment, a post-independence apartment,” he says. “It was demolished, and that site was sold for $1 billion.

“One billion at that site where you're seeing those horrible apartments. It's just the land value.”

A three-headed dragon

NUS professor of architecture and UNESCO chair on architectural heritage conservation and management in Asia Puay-Peng Ho points to three major issues for preservation: capacity issues with contractors and materials, a lack of informed government policy and a little public interest.

Professor Puay-Peng Ho's office is overrun by architecture books. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Professor Puay-Peng Ho's office is overrun by architecture books. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Dr Joshi says most resources for conservation projects need to be imported. His passion is palpable, his words flying fast without pause, as he explains how it’s not only authentic materials needed, but knowledgeable tradespeople to carry out the work.

“We are losing the craftsmen – we have lost like 99. 99 per cent,” he says, “So we have to rely on China, we have to rely on other countries.”

The ArClab graduate program wants to fix this by creating an ‘ecosystem of conservation’, training not only young architects, engineers, and contractors but also policy makers.

Minutes earlier, Dr Joshi was meeting with the director of the Urban Redevelopment Authority, the organisation responsible for land planning and conservation, to advocate for more developed conservation standards such as in bigger countries.

“We don't even have a proper guideline or a policy [about] how you should repair this building,” he says. “Our job is to educate even the policy makers.”

Professor Ho says the deficiency in government standards is due to a business-focused culture.

“I think conservation is kind of a learning curve for every government. The aim is noble, but the practice, it takes stages,” he says. “The culture here, both the business culture and the kind of societal culture, I think will be very different from say, the European culture.”

“In Europe you take conservation as kind of a must, or something that is like a normal kind of thing to do, but here, development is the key.”

ArClab research associate Elizabeth Yang says a preference for development is big amongst the public as well, especially younger generations who favour the concept of ‘progress’ over built heritage.

Elizabeth Yang listens as Dr Joshi explains ArClabs purpose. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Elizabeth Yang listens as Dr Joshi explains ArClabs purpose. Photo: Chloe Henville.

“We're very used to conservation being very clean, like in the sense that colonial buildings are all painted white. And there's this idea of progress means clean,” she says.

Miss Yang herself was only drawn to the conservation after studying one unit about it in university, changing the track of her career trajectory. She started studying at ArClab in 2022 as a master’s student, before taking on a research role.

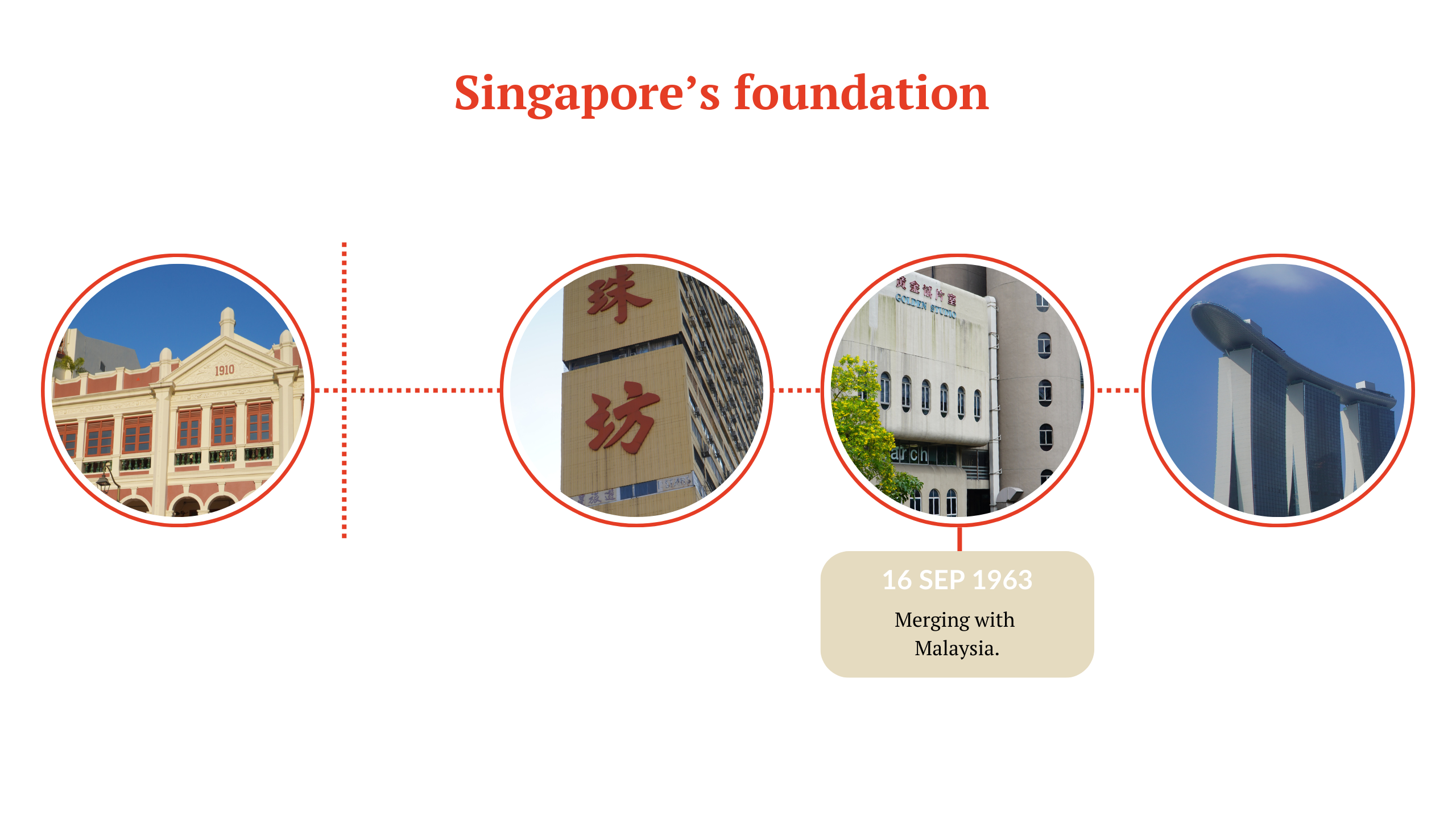

She says a multitude of attitudes are behind the community's lack of interest, including the country’s relatively recent independence in 1965.

A historic Chinese medical centre is still visible today. Photo: Chloe Henville.

A historic Chinese medical centre is still visible today. Photo: Chloe Henville.

A historic Chinese medical centre is still visible today. Photo: Chloe Henville.

A historic Chinese medical centre is still visible today. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Skyscrapers are visible over colourful shophouses. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Skyscrapers are visible over colourful shophouses. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Ornate details of a heritage temple. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Ornate details of a heritage temple. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Many architectural styles collide. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Many architectural styles collide. Photo: Chloe Henville.

“I find it's very common that we undermine our history because we are like, ‘oh, we've only been around for 50 plus years’.”

And multiculturism comes into play.

“Singaporeans also have this thing of ‘what is our Singaporean identity?’,” Miss Yang says. “Because we are all multi-racial and multi-religious. So, there is confusion in a way of what our culture actually is.”

This non-homogenous population plays into what is preserved, more specifically whose heritage buildings are preserved.

“We find that because Chinese are the majority in Singapore our things are very well documented. In a way, there are also a lot of Chinese in the conservation industry,” she says.

“Like this [ArClab] house was owned by a Straits Chinese family. This whole row was owned by rich Chinese families. So, because they were rich and they cared a lot about their roots, all their roots were well documented.

“Potentially the people with the more money and the more power have had their history and heritage preserved.”

A ‘dirty’ word

Professor Ho points to a societal sentiment of ‘survival’ for the historic lack of concern. He says Singapore took an economy-first approach as a result of the country’s geopolitics.

“I think if you ask him to prioritise, survival would be very high,” he says.

“My sense is that we have to build a civil society, before we are able to educate our public in terms of their roots, in terms of their identity, in terms of their past, and in terms of their aspiration to build a new society while keeping some of the best architecture.”

In the 2000s the Urban Redevelopment Authority chose ‘a simple guideline’ to maintain the façade of historic shophouses, while allowing flexibility inside, to not erode the investment value for potential buyers.

The URA's Singapore City Gallery shows models of shophouses and temples along Telok Ayer. Photo: Chloe Henville.

The URA's Singapore City Gallery shows models of shophouses and temples along Telok Ayer. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Professor Ho says this helped preserve 6,700 buildings, at the cost of original interiors.

“It's to what degree do you allow them to modernise and add new buildings to the old house, right?,” he says.

“And so I think we have gone a bit too far.”

Professor Ho also says the URA helps to oversee the construction of tall buildings in historic areas, with certain limitations to ensure they are not obtrusive from a street view. It’s a compromise, a fine balance between conservation and modernisation.

“Compromise is always a dirty word,” he says.

“But I would say that it's a kind of trying to accommodate modern living expectations and aspirations within the historical fabric.”

Heritage enthusiast and educational TikToker Yong Ho disagrees. He says this compromise can help connect the public with historic buildings. Mr Ho wrote a thesis which found turning heritage buildings into practical, frequently used public spaces created a deeper care and connection between the people and the history around them. Therefore, it may be more valuable to preserve only certain features and update others to fit modern living.

Yong Ho takes his passion of heritage and urban design to the streets. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Yong Ho takes his passion of heritage and urban design to the streets. Photo: Chloe Henville.

“I think keeping the facade and getting people to come explore the building again does have its value and I think people are enjoying it.

“It's a win-win situation to get a better understanding of the past.”

Mr Ho is trying to use his online platform @urbanist.singapore to foster support for heritage conservation. He shares short videos highlighting the stories of buildings, as well as hosting walking tours through Singapore. He’s seen exponential growth in interest, gaining more than 23,000 followers since starting his TikTok account around six months ago.

This could reflect the governments’ preservation efforts, helping residents to see the importance of the significant architecture around them.

Hard-won precedent

So, with limited land, skilled trades and materials available, how does Singapore decide what is worth keeping and what can be sacrificed in the name of advancement?

This beautiful building is nestled between businesses. Photo: Chloe Henville.

This beautiful building is nestled between businesses. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Tourists vist a temple on Telok Ayer Street. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Tourists vist a temple on Telok Ayer Street. Photo: Chloe Henville.

A charming shophouse. Photo: Chloe Henville.

A charming shophouse. Photo: Chloe Henville.

The Fullerton Hotel sits in the city centre. Photo: Chloe Henville.

The Fullerton Hotel sits in the city centre. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Ornate details of a temple. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Ornate details of a temple. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Heritage buildings may evoke images of elaborate temples such as the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple, or pastel hued shophouses of Koon Seng Road – maybe even reminders of Singapore’s colonial past such as the Fullerton hotel. But have you considered the 20th century post-Independence examples? The streamlined, no-nonsense designs of brutalism? Right now, these buildings may feel decades out of date but they’re a time capsule of the 1950s to 70s. Eventually artefacts from this time will also be considered heritage.

Dr Joshi, Professor Ho and Mr Ho all brought up a recent win for future heritage – the Golden Mile Complex. Resembling a giant concrete staircase, the 1973 brutalist building became a Thai community centre. Over time, it became an icon.

The step-like profile of the Golden Mile Complex. Photo: Sengkang distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

The step-like profile of the Golden Mile Complex. Photo: Sengkang distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

In the early 2020s, the complex was put to en-bloc sale, with 80 per cent of the owners agreeing to sell to the same buyer. It was likely to be a property developer.

“There has been a lot of of voices about retaining it, conserving it,” says Mr Ho.

“It was about to be demolished,” says Dr Joshi. “It was sold for 750 million… but the government said 'enough is enough'.”

NUS was approached to do a report on the cultural and environmental impact of removing the complex. With the findings, the government decide to conserve the building in October 2021. But to keep private developers' interest, it had to come up with compensation. The next-door carpark was earmarked for a 36-storey construction, an incentive to buy and maximise profits since the complex can’t be torn down.

Professor Ho says while successful, the Golden Mile Complex case is likely to be an anomaly in brutalism preservation.

“The government can preserve a privately owned property from the 70s, but there probably will be a handful of examples in the future. No more than a handful,” he says.

“Buildings will continue to be demolished unless the government passes a law.”

And it all comes back to money.

“The land is so precious… [the] government doesn't want to have a fight with the developers, because they are very powerful and rich,” says Dr Joshi.

A few houses down from ArClab, a shophouse is up for sale. Photo: Chloe Henville.

A few houses down from ArClab, a shophouse is up for sale. Photo: Chloe Henville.

Mr Ho says “I guess that's life in Singapore because we are ultimately constrained by our size. I think there has to be some kind of a balance between progress in terms of development and retaining heritage.

“I don't envy the government trying to do that though."